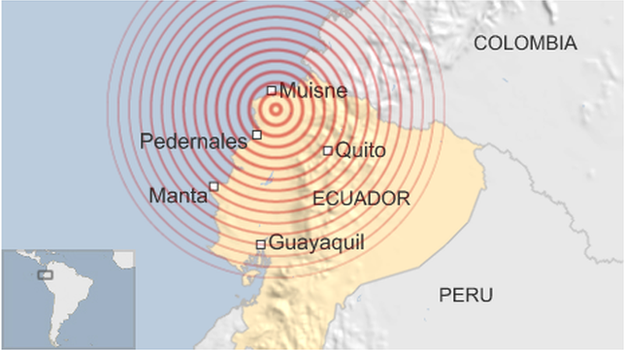

The 7.8 magnitude earthquake that rocked Ecuador on 16 April inflicted a grave human toll, including more than 600 deaths, 4,500 injuries and more than 25,000 people left homeless.

The earthquake, the most powerful to hit Ecuador in a generation, also wrought a level of economic devastation that would have proved problematic at any time for a developing South American country. But Ecuador, the smallest of the OPEC nations, was already in financial crisis, its reserves depleted by historically low crude prices and slumping markets for its banana and flowers exports.

Those economic conditions leave the country with only $300 million (£207 million) in an emergency fund, plus a projected $600 million from multilateral lenders, to pay for damages that could approach $4 billion (£2.8 billion).

“This isn’t going to take three days or three months,” President Rafael Correa told The Wall Street Journal. “This is going to take years …”

Insured losses could range from $325 million to $850 million, according to catastrophe modeling firm AIR Worldwide. The firm noted that those estimates are based on assumptions about earthquake insurance penetration rates in Ecuador, “about which there is considerable uncertainty.” Ecuador’s private earthquake insurance penetration rate is “low, even by regional standards,” according to LatAm Investor, a U.K.-based Latin America-focused investment magazine.

Faced with such a dearth of resources with which to rebuild, the government is resorting to tax increases for the needed capital, raising its value added tax from 12 percent to 14 percent and imposing new income taxes.

People with assets worth more than $1 million will pay a one-time assessment equal to 0.9 percent of their wealth, while the masses will contribute a day’s salary. Those earning less than $1,000 per month will make the payment just once, people earning $2,000 a month will pay it monthly for two months, and those earning $5,000 or more monthly will pay it monthly for five months.

The government also will sell off unspecified assets.

While Ecuador’s earthquake insurance penetration rate is reportedly low, it could be growing, depending on how many Ecuadorian homeowners and businesses are opting to supplement their policies with an earthquake coverage endorsement. Such opportunities have certainly increased in number, as general property insurance penetration in the country grew by 20 percent from 2010 to 2015, according to a report by Timetric.

While Correa’s tax increases will likely generate enough revenue to fund reconstruction, the trade and tourism sectors have been hit hard, and there is uncertainty about the country’s economic future. The leftist president’s public welfare spending was robust and popular during the oil boom but the government failed to set aside any reserves for the rainy day that it’s now experiencing.

Some analysts worry that the tax hikes will further slow the already struggling economy as costs for materials rise. Also, uncertain is the future of insurance reforms Correa has tried to implement.

The government in March 2015 announced that insurance carriers operating in the country may no longer cede more than 5 percent of their premiums to reinsurers outside of the country, an effort aimed at keeping more money in Ecuador. But the insurance industry, which sends up to 50 percent of premiums to foreign reinsurers, has strongly opposed the measure and compliance has been slow.

Insurance companies initially were required to meet the new 5 percent threshold by March 2016, but on April 14, just two days before the quake, the government announced an 18-month extension for compliance.