Each new student loan issued launches another person toward learning, self-discovery and a career.

Unfortunately, each new loan also triggers what many observers warn is another tick of the student debt time bomb.

Others liken swelling student loan debt to a bubble that could burst at any moment.

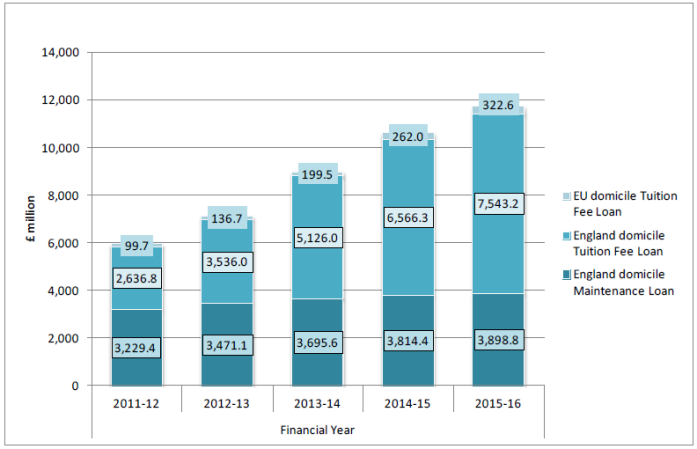

Whatever the analogy, it’s easy to see why experts are concerned. As the United Kingdom has reduced its subsidies for tuition, student loan lending has nearly doubled over the past four years, jumping from about £6 billion in 2011-12 to £11.8 billion ($16 billion) in 2015-16, according to the Student Loans Company.

That brought the total U.K. student loan balance up to £76.3 billion in 2015-16, an 18-percent increase from 2014-15.

A growing number of students are not repaying their loans, a truth that threatens to leave the government high and dry. After 30 years, the loans are written off.

Student loans debt has long been mounting but a big change in how the United Kingdom calculates interest, effective in 2013, has created much of the problem. Instead of paying just 1.5 per cent interest as they had been charged, student loan borrowers since autumn 2013 have been paying a rate equal to the Retail Prices Index plus 3 per cent – a total rate around 6.3 percent.

Only about 15 percent of students are likely to repay their loans from income alone

Under the current rates, because of compounding interest, only about 15 percent of students are likely to repay their loans from income alone, Tonbridge School researcher Dr Mike Clugston has told The Mail.

That is considerably worse than the 40 percent of loans the government initially projected will be repaid, an alarming figure in itself.

So, what’s the risk? Can students just keep piling up loan debt forever?

For one thing, Millennials, or those aged 18 to 34, are having a harder time than previous generations buying homes, partly because of their student loan debt. Graduates in the UK must start making repayments when their incomes reach £21,000 which equal to 9 per cent of their income above £21,000.

While most graduates will never fully pay back their loans, the 30 years of repayments they must make effectively constitute a tax. That millstone around their necks makes it harder for them to get on the housing ladder.

Another reason to worry about the new trends in student lending is the effect they will have on government coffers. When the government decided to allow U.K. universities to triple their tuition from £3,000 per year to £9,000 per year, despite heated student protests, it projected the new system would cost less as long as at least 48.6 percent of loans are repaid. But as we’ve discussed, analysts say the government has been far too optimistic with its projections.

As precarious as the situation might seem, the U.K. government is at less risk of students failing to pay back their loans than their counterparts across the pond. A major reason lies in how the two countries differ in their collection systems. U.K. borrowers typically have their repayments withdrawn directly from their payroll, while Americans usually make loan payments on their own.