Journalists around the world have only just started to wade through the massive data leak dubbed “The Panama Papers,” but one thing is already clear:

There has been a public rush to condemn the tax avoiders as unequivocally immoral. How dare these wealthy and politically elite individuals and corporations move their money off shore in order to lower their tax burden, the critics charge?

The political fallout from public consumption of the 11.5 million files is just beginning. Within two days of their release, hacked from the woefully outdated and unprotected computer network of global law firm Mossack Fonseca’s Panama City offices, Icelandic Prime Minister Sigmundur Gunnlaugsson resigned. Documents linked him to an offshore company.

Also sullied was British Prime Minister David Cameron’s late father, found to have enlisted Mossack Fonseca’s expertise in sheltering his investment fund, Blairmore Holdings Inc., from UK taxes.

The Prime Minister himself has denied any such involvement, but the tangential connection was unwelcome at a time when Cameron has called for austerity in the face of declining tax revenues. Thousands of protesters called for his resignation on Saturday 9th April after his revelation that he had bought and sold shares in his father’s fund, the Daily Telegraph reported.

Mossack Fonseca founder Ramon Fonseca has maintained that his firm has broken no laws, denouncing the hack as a “witch hunt” by activist journalists. He told Reuters that the firm has set up more than 250,000 businesses for clients over the past 40 years, insisting that their “standards are very high.”

“I guarantee you we will not be found guilty of anything”

“I guarantee you we will not be found guilty of anything” Fonseca told Reuters.

Such confidence is likely well-founded. The Panama Papers leak has quickly heightened awareness of the need for much better cyber security, but it has also triggered another discussion that is equally important: There is a clear difference between tax avoidance and tax evasion.

Tax avoidance is generally described as legal manoeuvring to reduce one’s taxes, while tax evasion involves breaking the law to achieve the same end.

Since the Great Recession of 2008, tax havens have been coming under heavier scrutiny. As the wealth gap continues to widen around the world, the masses are becoming less tolerant of the rich not paying their fair share of taxes.

Some observers view this climate as the launch of an all-out assault on capitalism. After all, when corporations avoid taxes to maximise profits, they are simply fulfilling their fiduciary duty to shareholders. To decry that practice is to question the very underpinnings of globalisation and the capitalist system, argue many on the Right.

A second argument advanced by this sector is that tax avoidance and even evasion are good for society because, contrary to popular opinion, they result in lower taxes for everyone else.

Tax avoidance proponents, already weary of the moral harrumphing surrounding the Mossack Fonseca leak, argue that if politicians are as disdainful of avoidance as they claim, they alone have the power to write laws restricting it, yet they have failed to do so.

Still, in Great Britain, a YouGov survey found that 62 per cent of people found legal tax avoidance “unacceptable.”

It is, and has for a long time, been deeply entrenched in nations around the globe. The Guardian has reported that the Panama Papers shed new light on how Russian President Vladimir Putin’s inner circle used Mossack Fonseca to hide millions of dollars in a variety of schemes. Putin, in turn, has sought to deflect the attention, chiding U.S. President Barack Obama for looking the other way while corporations seek haven from taxes in the state of Delaware.

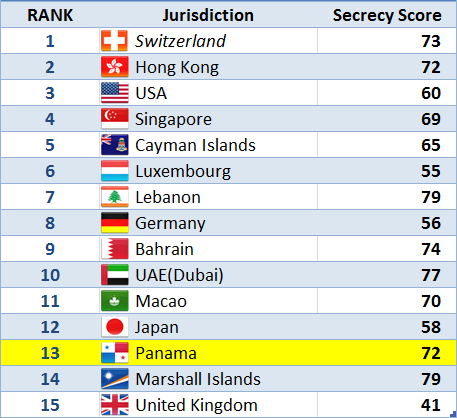

Likewise, Fonseca told Reuters that it is cheaper to do business in Nevada than in Panama. The South American country ranked just 13th in the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index. The five most secretive nations, respectively, were Switzerland, Hong Kong, the United States, Singapore and the Cayman Islands.

The scandal threatens to overshadow the G8 summit on tax avoidance that David Cameron will host next month in London, a follow-up to a 2013 summit in Northern Ireland in which the prime minister vowed to crack down on the practice.